The beloved animated movie Balto was based on the true story of Balto. But the film significantly increased the amount of fantasy in the already epic story. The years of tragedy that befell Balto after his victory were not included in the film version. The most heroic dog stories are frequently seen in American children’s films and television, including Scooby-Doo and Air Bud. However, in the case of Balto, the truth must be spoken as emphatically as the wolf howl of his fictitious counterpart.

The Balto movie emphasizes certain fiction because it is intended for children, such as Balto’s goose friend, female love interest, and bad dog foe. In the movie, a diphtheria outbreak threatens a hamlet in Alaska, and the only hope for survival is an anti-toxin that can be found 1,000 miles away. This parallels the real-life tragedy of Balto. Balto lends a hand as he did in the movie because the Nome residents decided to employ dog sleds to get the serum as soon as feasible. However, Balto’s adventure didn’t exactly go as the creators had intended.

Putting aside the grizzly bear battles, altering the actual events of the story left out the many other human and canine heroes that helped deliver the serum, whether the intention was to make the story even more interesting or capture kids’ imaginations with a cute dog movie.

Every youngster from the 1990s remembers the movie Balto, but the real-life account of the brave dog is even more moving.

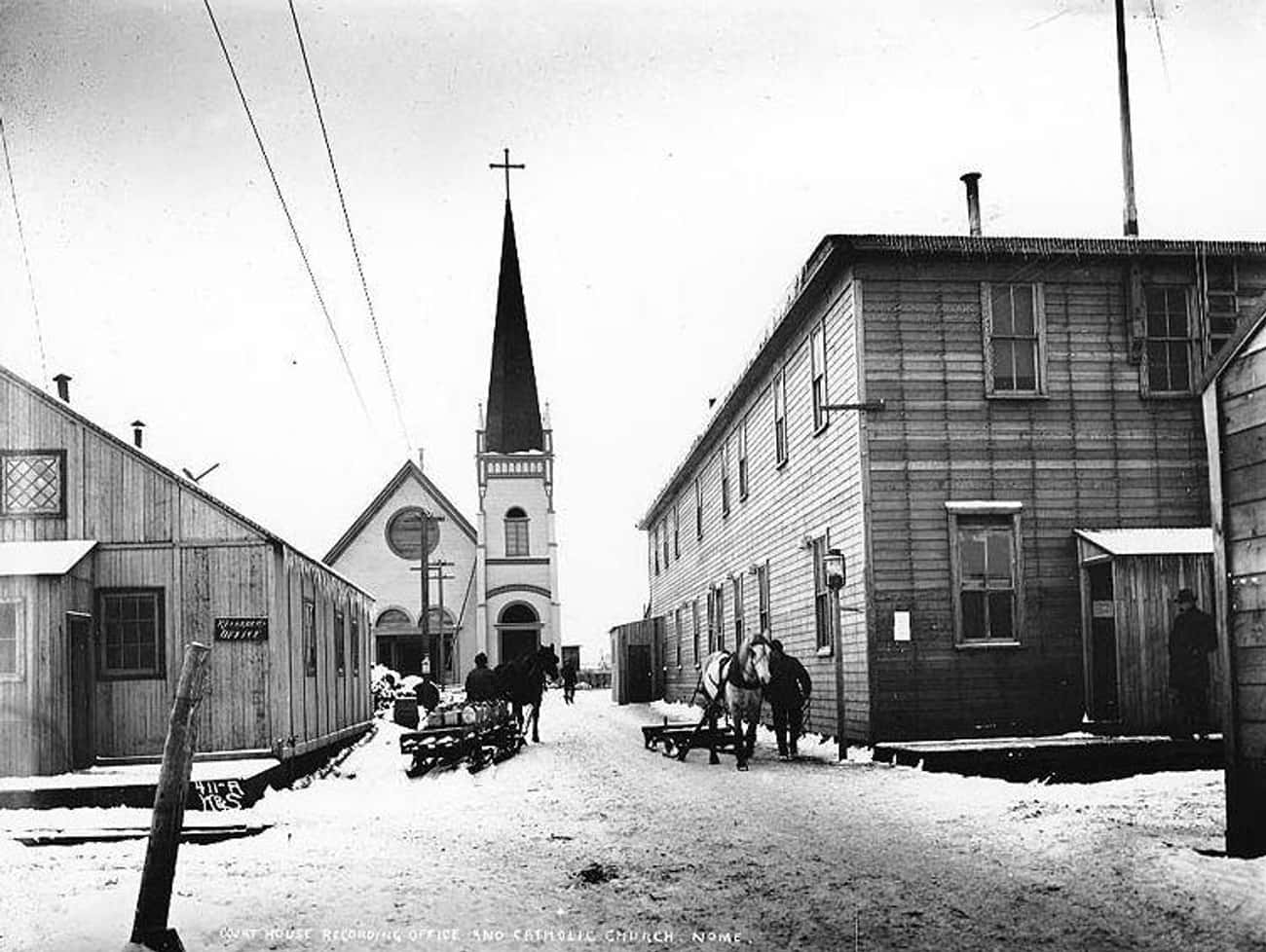

Balto’s hometown of Nome, Alaska, was threatened by a Diptheria outbreak in 1925.

Diphtheria, a respiratory illness, was contracted by numerous kids in Nome, Alaska in January 1925. Because the disease was so nasty and very contagious, people feared getting sick. The youngsters were confined by the town’s sole physician, but he was concerned that other inhabitants would also contract the disease because of how swiftly it spread.

To make matters worse, Anchorage, Alaska, which was more than 1,000 miles away, was home to the closest source of antitoxin serum. In the bitter cold, flying was out of the question, and the harbor’s ice counted out vessels.

The people of Nome began using a more traditional mode of transportation—the dog sled, which had long been utilized for mail delivery.

Extreme weather was overcome by dogs and mushers to get the serum safely home.

To get the serum, a dog sled team would have to travel for weeks. The villagers made the decision to set up the operation as a relay to combat weariness. The prior team might then take a break once one team picked up the serum from a checkpoint. More than 20 mushers contributed to the project.

The 20-pound container carrying the serum was taken up by the first team, which was led by “Wild Bill” Shannon. 52 miles were covered by him and his team in minus-60 degrees cold while moving just quickly enough to prevent the formation of frost on his dogs’ lungs.

The longest segment of the trip, at 91 miles, was completed by Leonhard Seppala and his lead dog Togo. Seppala made the decision to take the short path, braving winds that threatened to blow them off course and temperatures of minus 85 degrees while moving across slick ice. They reached the following musher safely, who eventually delivered the item to Gunnar Kaasen and Balto, his lead dog.

The serum arrived in Nome in less than six days, compared to the 25 days it may have taken the regular mail service.

Balto was invited to Hollywood by a film producer to appear in movies.

Balto soon rose to fame as a result of the media’s close attention to the relay. Leonhard Seppala, the owner of Balto, thought the praise was unwarranted given that more than 150 other dogs also took part, including Togo, who finished the longest portion of the trek.

Nevertheless, Seppala gave permission for Gunnar Kaasen to transport Balto and his crew to Hollywood, where producer Sol Lesser supported the production of the 30-minute movie Balto’s Race to Nome, which starred the new dog star.

The real Balto wasn’t considered to be the best lead sled dog because he wasn’t a part wolf.

The Siberian husky Balto from the animated movie is half wolf; the genuine Balto is said to have been born in 1919. Balto has a white patch on his chest and paws and a black coat overall.

Even though the real Balto did not lead an isolated existence, he was not regarded as the best lead sled dog. But because of Balto’s muscular physique and barrel chest, Seppala hired him to serve on the miner sled team.

When it was time to start the serum, Gunnar Kaasen gave Balto a chance, while Seppala selected Togo as his lead dog.

In A Sideshow Museum, Balto And His Team Eventually Felt Neglected.

Balto and his group eventually wound themselves in a carnival in Los Angeles where visitors could watch them for a dollar. Balto and the other dogs were mistreated, imprisoned in the sideshow museum, and left there until a different buyer came along.

At the Cleveland Natural History Museum, guests can see Balto.

The Cleveland Brookside Zoo donated Balto’s body to the Cleveland Natural History Museum upon his passing. His body had been stuffed, displayed, and preserved for posterity. Balto was given his own contained exhibit by the museum so that visitors could see him.

A bronze memorial honoring Togo, another dog sled hero, as well as Balto was built in the Cleveland Brookside Zoo.

Alaskans desire to display Balto at their local Iditarod museum.

A group of young Alaskans longed for their beloved hero to return home in the 1990s. They organized a campaign in an effort to get the Cleveland Natural History Museum to lend them Balto so they could show him at the Wasilla, Alaska-based Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race Museum.

Balto lived in Cleveland for the majority of his life, so why should they accept him? They argued.