Tokitae the orca plans to return home, more than five decades after being captured in the waters of the Pacific Northwest, giving a victory to animal rights advocates and Indigenous leaders who have long fought for her release.

On Thursday, the owners of the Miami Seaquarium, where Tokitae resides, declared that they had reached a “formal and binding agreement” with a group called the Friends of Lolita to begin relocating Tokitae to Puget Sound. According to a press release, the collaborative effort is “working towards and hoping for the relocation to be possible in the next 18 to 24 months.”

Tokitae, the oldest orca

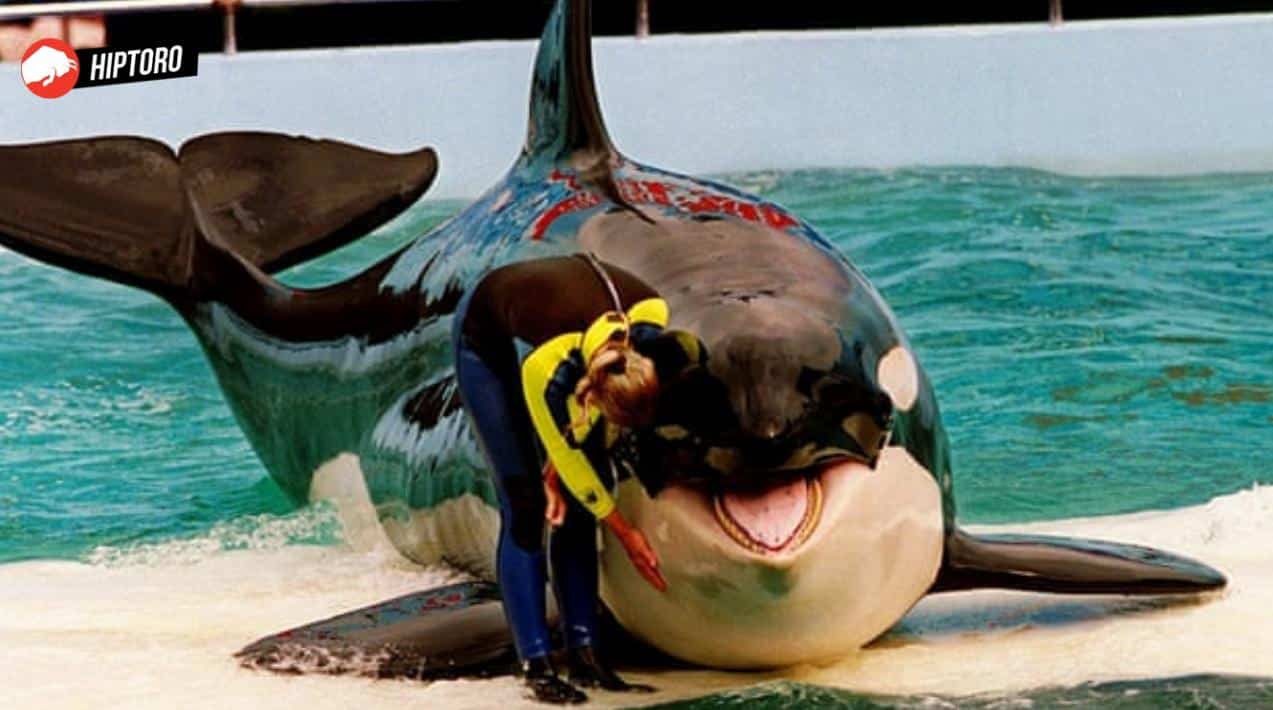

Tokitae is the eldest captive killer whale. She is now retired after spending decades acting at the Miami Seaquarium as Lolita. She resided in the smallest orca enclosure in North America, in a pool of water that infected her skin and fed fish that was occasionally rotten, causing intestinal problems.

Several groups, including Lummi Nation members and animal rights organizations, have called for the whale’s release from the Seaquarium over the years, with some staging demonstrations outside the facility.

Jim Irsay, the owner of the NFL’s Indianapolis Colts, made a “generous contribution” that helped alleviate financial concerns about Toki’s prospects. “I know she wants to get to free waters,” Irsay said at a press conference in Miami on Thursday. “I don’t give a damn what anyone says. She’s waited this long for this chance.”

Tokitae’s ordeal started five decades ago in the calm waters of Penn Cove on Whidbey Island, a quiet island off the coast of Washington State. Men wielding long sticks and firearms apprehended a group of resident killer whales, separating mothers and calves. At least a dozen whales were killed during the capture, and more than 50 were held in captivity for display.

Tokitae, a four-year-old calf, was one of those heifers. Back home, the original Lummi people refer to her as Sk’aliCh’elh-tenant, which means she is a member of Sk’aliCh’elh, the resident family of orcas who live in the Salish Sea. The tribe considers killer whales to be members of their extended family and has never given up battling for her release.

Toki’s health and ability to move across the country to a sea pen remain unknown. The pen would be built with the assistance of the non-profit Whale refuge Project, which is also making the world’s first whale refuge off the shore of Nova Scotia, modeled after areas that house big cats, great apes, or elephants after they have been in captivity.

Toki’s relatives, members of the Salish Sea’s resident L-pod, are still living, including the 90-year-old whale thought to be her mother. Experts are concerned that if Toki comes into contact with her relatives, even through a sea pen, the infections she took up in confinement could be passed on to other southern resident killer whales, a critically endangered species with only 74 individuals.

Federal agencies must approve any preparations to transport the whale. Of course, the stress of travel and being in a new, wild habitat could be hazardous to an elderly whale.

Nonetheless, Thursday’s decision is historic. Howard Garrett, founder of the non-profit Orca Network and long-time advocate for Toki’s release, says the news was vague but set the tone for unified purpose and action. “That’s what’s going to make it happen.” That will significantly impact agencies, skeptics, and naysayers,” he adds. “This was a watershed moment in history.”