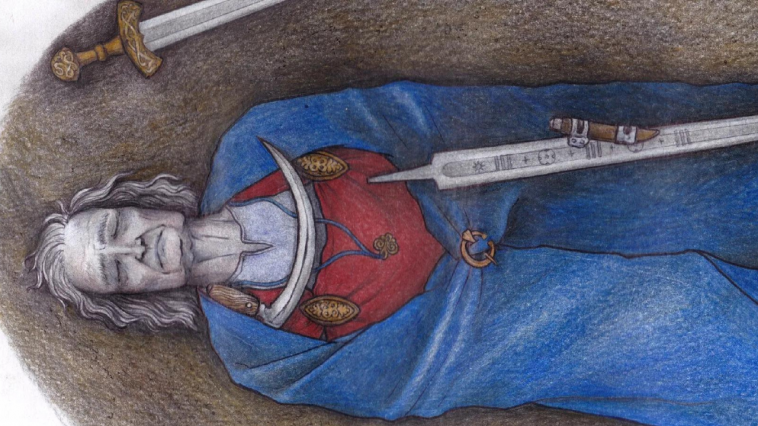

A warrior buried 900 years ago could have been non-binary.

Around 50 years ago, the remains of a warrior armed with a sword were discovered in southern Finland.

Archaeologists recently revisited it, and it appears that an interesting development has occurred.

Due to the warrior’s traditional clothing and jewelry from the time, the remains were considered women.

However, the warrior was buried with two swords, often associated with masculinity in many pre-modern European cultures.

Researchers discovered, however, that just one sword belonged to the original burial site.

The other weapon, known as the famed sword of Suontaka, was most likely buried at a later date near the spot.

Some academics suggest that this could be owing to a lady and a man being buried together.

The Warrior

However, after further examination, archaeologists discovered that the warrior appeared to have an extra X chromosome (XXY).

The ancient DNA examination of the remains was carried out by a team from the University of Turku, the University of Helsinki, and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

The DNA was severely degraded, but the findings suggest that the buried individual may have been born with the sex-chromosomal aneuploidy XXY, also known as Klinefelter syndrome.

The hereditary disorder Klinefelter syndrome causes males to be born with an extra X chromosome.

The symptoms are frequently modest, and some people go through life unaware that they have this disorder.

Infertility and tiny testicles are the prominent symptoms, although other symptoms include increased height, broad hips, decreased muscular mass, decreased body hair, and the growth of breasts.

Some people with Klinefelter syndrome may also have trouble socializing with others and expressing themselves.

In a press release from the University of Turku, Elina Salmela – from the University of Helsinki – says: “According to current data, it is likely that the individual found in Suontaka had the chromosomes XXY, although the DNA results are based on a very small set of data.”

While it is difficult to know how others regarded these warriors, their burial demonstrates that they were well-respected.

Ulla Moilanen, study author and Doctoral Candidate of Archaeology from the University of Turku. explains: “If the characteristics of the Klinefelter syndrome have been evident on the person, they might not have been considered strictly a female or a male in the Early Middle Ages community.

“The abundant collection of objects buried in the grave is a proof that the person was not only accepted but also valued and respected.

“However, biology does not directly dictate a person’s self-identity.”